Rafał Bujnowksi -- Portraits

Abstract art was born out of the night. A spark that set off the artistic revolution was the play between darkness and light that occurs after dusk. “By using the word 'nocturne' I wished to indicate an artistic interest alone, divesting the picture of any outside anecdotal interest (…) A nocturne is an arrangement of line, form and colour first” – these words of James McNeill Whistler from his famous court battle against John Ruskin are widely considered the first conceptualization of non-representational art. His night landscape of a park lit by fireworks was debased by the popular Victorian critic as “a pot of paint flinged in the public’s face”. For him the alleged accidental character of the brushstrokes made it nothing more than a stain, a wasted art supply. The American painter fiercely opposed this view in the courtroom, presenting his artistic method as parallel to that of a composer meticulously orchestrating the subtleties of tone.

As a conceptual painter inspecting inner workings of his medium, Bujnowski loves posing old questions and finding new answers. He has had a soft spot for both Whistler (Whistler’s Mother painting, 2002) and the ‘nocturne’ genre he named and championed for quite a while. His Dusk. Video painting (2004) series, in which he paints over landscapes transforming them into monochromatic abstractions, can be seen as a simple Whistlerian lecture on how every evening the figurative order of things melts into the air. The tension between figuration and abstraction is always present in his works, with special attention focused on the role the different sources of light play in the process. In Landscapes (2010), Nocturne – Graboszyce (2012), and the more recent American Night (2022) series, he explores how real and fake (cinematic) moonlight can operate within the picture. In Arsonists (2013) he draws austere human silhouettes illuminated by fire with a single line of chalk on a blackboard. Finally, in the Standby Computer (2021) and Portraits (2019) he arrives at the source of artificial light emblematic of our century – the screen of mobile devices.

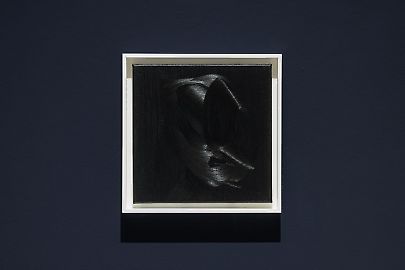

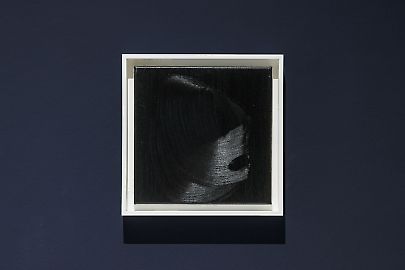

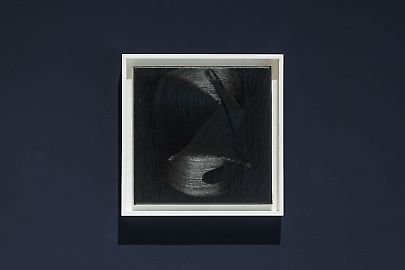

Yet, unlike his American predecessor, Bujnowski embraces randomness and materiality, making them the guiding principles of his art. Portraits are a perfect example of how the theme derives from the matter. In the series of intimate works painted with thick, spatial impasto strokes, he follows the qualities of the tools: a broad brush and his favorite lamp black paint, as well as the way they interact with external sources of light in the exhibition space. The visual associations emerge in the process – both on the side of the artist and the viewer. Seeing female heads in the light of a smartphone screen in these elegant abstract forms can be associated with the trait of the human brain, known as pareidolia. It makes people look for representation even in random abstract forms like clouds or stains. And when we are in the darkness, our vision does exactly the same – struggles to recognize familiar objects to make us feel safe. Thus, the only difference between Victorian and contemporary nighthawks might be the easiness of the switch between two modes of perception, with a cold light of a phone always at hand.

Zofia Czartoryska